The article is written by Simon Gore, Managing Director at Holmes and Marchant, UK

Newton called it standing on the shoulders of giants; for Pablo Picasso, good artists copy, great artists steal; but perhaps US film director Jim Jarmusch summed it up most pointedly: “Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination… Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is non-existent.”

That might seem rather an extreme view, but we in the creative industries realise pretty early on that indeed, nothing is original, and the most successful design comes from brands and agencies that are willing to steal. Of course, outright stealing and adapting isn’t celebrated, especially not in design. In the main, this is because stealing in the design world is often confused with copying. Yet the two are poles apart, which is why there’s a strong body of thought that believes that stealing—or perhaps more accurately, intelligent borrowing—specifically from nature, is an efficient and inspirational path to that holy grail of marketing: innovation.

Taking ideas from nature and adapting them to the design conundrums of life—biomimicry—isn’t new and is now a common stamping ground for some of the big corporates, which are using the approach to bring biologists, industrialists, inventors and designers together at the drawing board to take a revitalised approach to new product development.

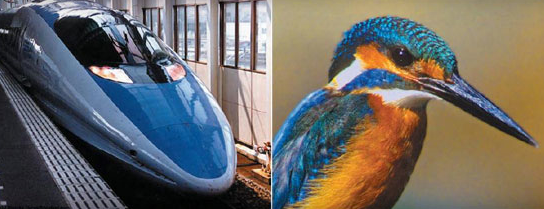

Photo: Japanese Shinkansen train mimics the beak of a kingfisher bird, from CNET

It’s obvious why. Biomimicry presents a compelling prospect: study nature’s best ideas and then imitate and adapt these designs to solve human problems. The concept operates on the principle that in its 3.8 billion year history, nature has already found solutions to many of the problems we are trying to solve. Based on the ideas and designs which nature has demonstrated to be successful, biomimicry is able to provide a wealth of inspiration for problem solvers—something that designers do every day. From Velcro, which is modelled on burrs from the Burdock thistle, to the Japanese Shinkansen train, modelled on the beak of a kingfisher, or Speedo, which uses sharkskin-like technology for extra streamlined qualities to develop Fastskin, the applications are many, varied, and nothing less than innovative.

Yet despite the obvious advantages, for pack and branding specialists, biomimicry remains a little-trodden path. We’re under such pressure to break from the norm, to stand out, to be different, to innovate, and yet we seek inspiration from the same old sources.

For branding and pack specialists, the notion of borrowing from nature presents an endless and ever-growing source of inspiration. For us, nature serves as a means to inform our thinking, rather than something to emulate. At the very least, adopting a biomimic approach appeals to the human sense of the familiar—we are creatures of habit and nature offers us an unbeatable reference point, an inherent way of making sense of things.

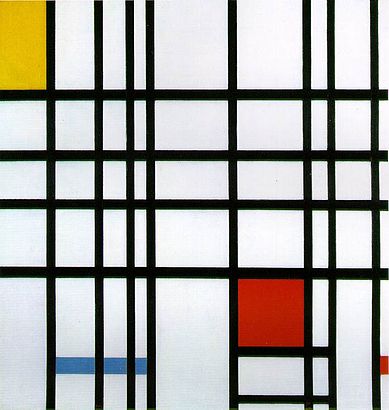

Pic: Piet Mondrian’s painting «Composition of Red, Yellow and Blue»

Photo: Mondrian-inspired L’Oreal’s Studio range

Brands already borrow reference points from everywhere else— from art, like L’Oreal with its Piet Mondrian-inspired hair product range, Studio; from science, like ABSOLUT and Hendrick’s Gin with their medicinal, apothecary styled bottles; or adjacent categories, as Apple did with its own products, iPhone and the Mac, combined to create the iPad.

We should add nature to that list. Great design and remarkable brands are directly related to designers who have embraced curiosity, who have taken inspiration and principles from new and unusual sources rather than the same old, same old.

So while it’s important not to recreate the wheel, to understand the vital difference between merely copying and stealing in the inspirational sense, it’s just as important to celebrate the basic fact of life that foundation blocks for nearly everything already exist. There’s nothing wrong in taking those blocks and putting your own stamp on them. And as Jarmusch concluded: “Don’t bother concealing your thievery — celebrate it, if you feel like it.”

About the Author

Simon Gore is Managing director at Holmes & Marchant, London office.

Holmes & Marchant, founded in 1967, is part of the privately-owned MSQ Partners, a group of leading creative and communications agencies and is supported globally with partner offices in Singapore, Mumbai and Shanghai. Clients include Kraft Foods, Unilever, Freixenet, Keyline Brands and Pernod Ricard.