With social media platforms, it has become yet easier to support social good causes with minimum effort. Today you don’t need to come out protesting in the rain, sign petitions, find a charity box to drop your nickel in, hand out leaflets or organize meetings to tell about a certain problem. Now, a person’s engagement into the problem can be expressed through a couple of clicks, or—most frequently—mere ‘likes’. This saves much more time and effort than participating in traditional public actions. With an obvious positive effect of this new-era tools for involvement, the actual value of such contributions is highly questionable. Still, liking may build the ground for socially good actions in a wider perspective.

Slacktivism: what is it and what forms does it take?

The British & World English dictionary defines slacktivism as “actions performed via the Internet in support of a political or social cause but regarded as requiring little time or involvement.” This term, which emerged in early 2000s, was coined from two words “slacker” and “activism” as a response to the growing popularity of online campaigns, mainly on Facebook and sign-a-petition platforms.

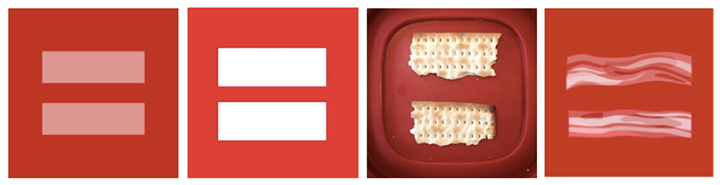

Such initiatives range from the simple “like us” requests to the calls to sign a letter in support of a social or environmental cause (Change.org, Avaaz.org and One.org are the most popular petition platforms) or change profile pictures (the LGTB rights’ pink-on-red equal sign icon, the red, black or pink ribbons, etc.). In general, another example of slacktivism is brands’ campaigns that encourage users to like some sustainability-focused effort, triggering a standard $1 donation from the business for the cause. It stimulates the audience to be generous on the brand’s behalf and kills two birds with one stone—consumers feel satisfied with themselves and brands strengthen their “good-doer” image.

While a lot of organizations and brands just encourage their fans to click and like, a number of brands add a dose of gamification to the process thus requiring users to do more than just clicking. For instance, Levi’s WaterTank game and Gillette’s Capture Your Mo’ activation offer donations to social organization in return for users’ engagement in the form of taking up online challenges or uploading photos. But still, no direct physical or financial help from consumers is supposed to be received here.

Why is slacktivism usually criticized?

The major reason why slacktivism has a negative connotation is because it provides “low-calorie” engagement. At best, campaigns that seek likes raise awareness about the problem and mirror the audience’s general intention to support the cause by simple “back patting.”

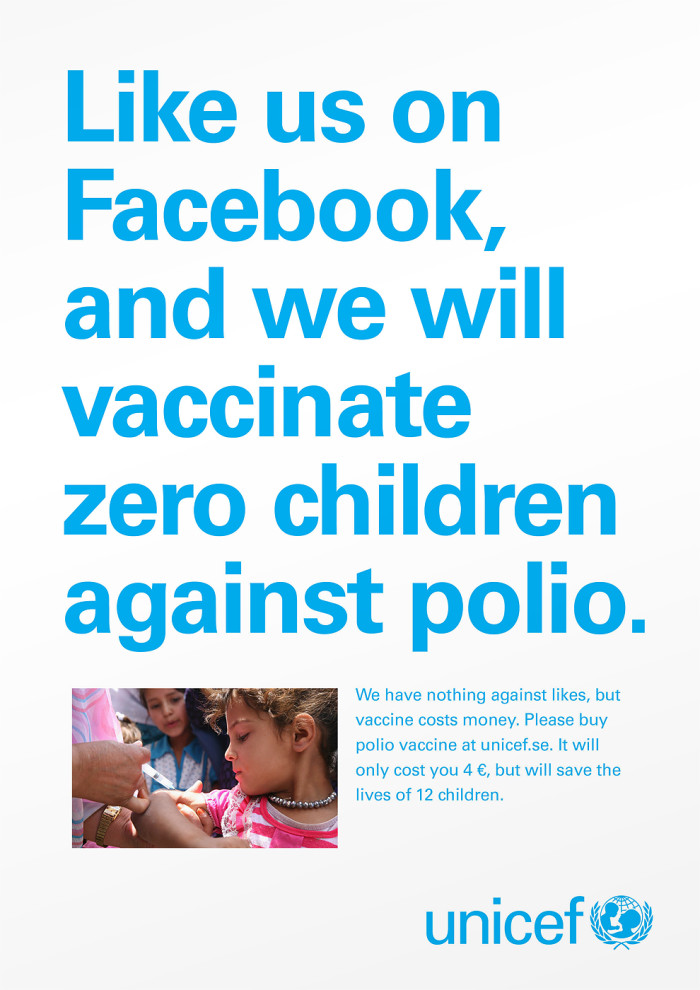

Will the thumb-up sings and shares buy food or cure? Will they teach a child in a rural African region or directly prevent deforestation? Of course, not. This has become the idea behind UNICEF’s ironical campaign titled “Facebook Likes Don’t Save Lives” in which the humanitarian organization encourages the audience to commit to tackling the global problems with more traditional actions—by donating money, not likes. The worldwide network of 125 international NGOs is urging people to donate their money directly to the organization to buy polio vaccines.

In the era when an average online user feels the over-saturation of incoming information, it doesn’t seem that the audience will support the causes they “liked” online with actual actions offline—they may not even remember all their clicks. The problem of many online cause-endorsing campaigns is that they build up a community of followers, which may actually not be part of the real movement—we may have an illusion of support instead of tangible help.

Slacktivism is often confused with so-called “suckerism,” a hollow activity that is all about sharing photos of dying people with a short text saying something like “share the photo and Facebook will donate a dollar.” This silly activity described by Digital Trends undermines digital activism in general and demonstrates users’ ignorance of how real donations can be made.

How can slacktivism do good?

The series of videos from UNICEF clearly communicates the idea of how hollow and useless mere liking might be. But in fact, slacktivism can be a fertile soil for growing deeper engagement that transcends online media. It also helps raise awareness and de-stigmatize diseases and behaviours among communities. While digital “like it” campaigns don’t necessarily bring money, they may inspire the followers to donate next time when they are directly asked to.

A study titled “Does Slacktivism Hurt Activism? The Effects of Moral Balancing and Consistency in Online Activism,” by researchers at Michigan State reveals that in fact online activism in support of social causes may be quite effective. The researchers dived deep into the behavioural patterns to discover that there are two factors to guide online activists to donating: moral cleansing and consistency. It was found that performing one form of slacktivism doesn’t have negative impact on the subsequent civic action. On the contrary, slacktivism can increase likehood of participation in such an activity (consistency), but it doesn’t increase the amount of money donated. Still, those who are invited to participate in a digital activation but decline to do so, subsequently donate more to an incongruent charity (moral cleansing).

In other words, organizations can use slacktivism to drive people from liking to donating simply by making them feel guilty. It’s a slippery rail since here charities are taking on people who actually make these micro donations, and if the pressure is too high, the digital activists will be discouraged and won’t go any further. With its campaign, UNICEF definitely targets the people who have already liked its Facebook page or the dramatic videos to make the next step, which resonates with the idea about online activists’ consistency.

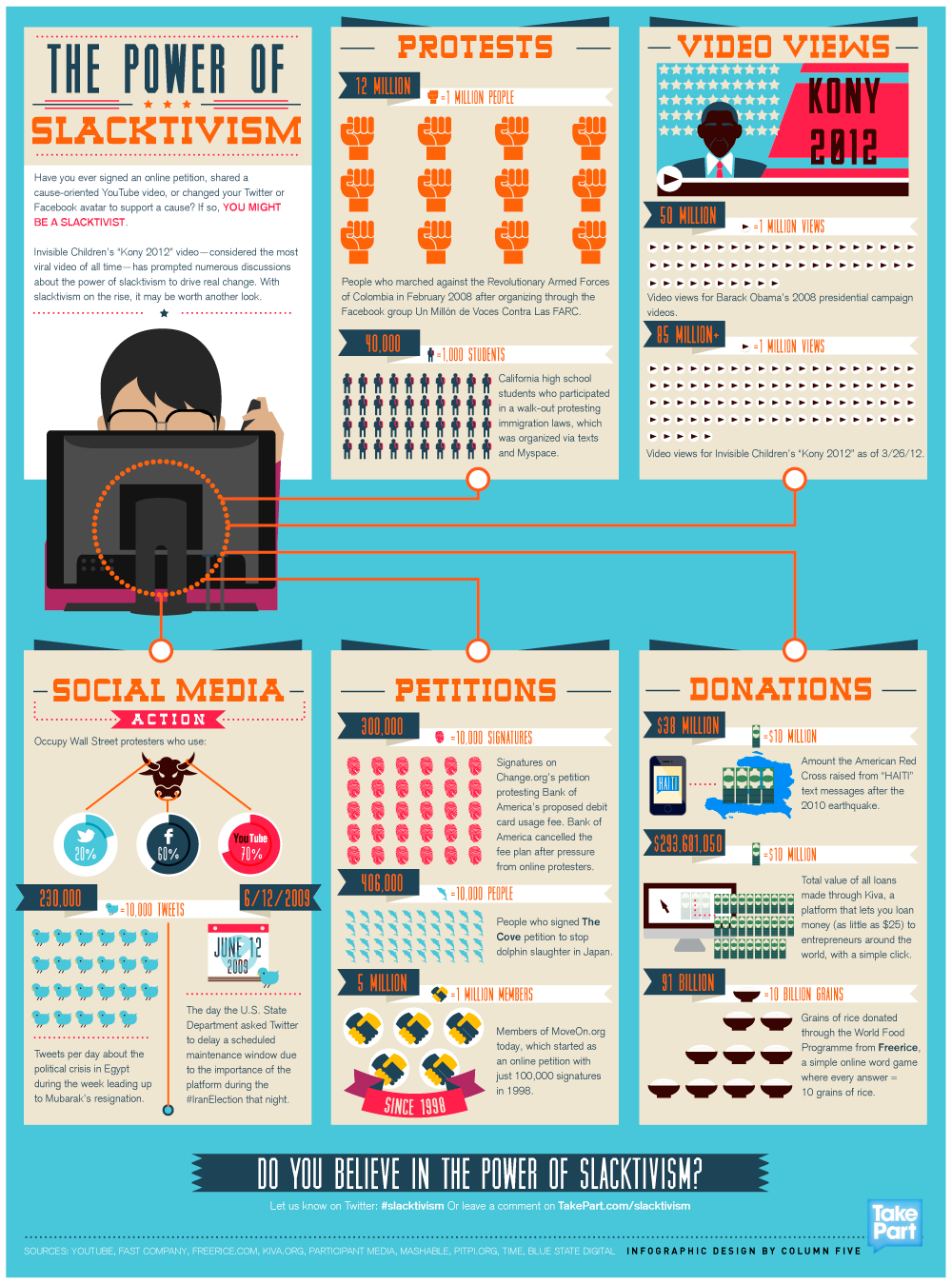

Read more about facts and feagures on slacktivism in the infographics below.

Three key positive facts about slacktivism:

1. The number of slacktivists supporting some social issue comes as a barometer of social interest towards this issue. With more effort from the campaign designers digital activists can become benefactors/volunteers in real life.

2. Moral cleansing effect can be used to drive donations. Create an excessive online request for the issue A that is likely to be not supported by the audience. Then, launch another initiative, B, in the unrelated domain. People, who will feel guilty of turning down the A issue, will more eagerly support the issue B.

3. Slacktivists usually do what they are asked. Ask more and they will do more. To garner financial support through micro donations, “enhance” the call by adding the “Donate” button, a link to the correspondent site, a step-to-step guide of how to contribute to the tacking the issue. Each charitable campaign should also have a transparent donating scheme so that people could understand where the money goes and see the effect of their actions.