Why to buy something if you need it for a limited time only? It’s much easier (and more rational) to share underused assets instead of purchasing and owning them individually. The past few years have witnessed the rise of what’s called the sharing (share or shared, collaborative, peer, access) economy which implies collaborative consumption of physical, virtual and intellectual goods. The new model of consumer relationship emerges at the intersection of online social networking, mobile technology and the social movement that comes as a response to the reduction in purchasing power. While the concept of the sharing economy seems to be clear, it needs some detailing. Why is the sharing economy good to people? What threats to traditional business can it pose? Does the collaborative consumption have a potential to become a consumer religion of tomorrow?

The collective owning: inspired by anti-consumerism, driven by social media

The new game-changing movement started to gain momentum since late 2000s as a response to the global financial crisis and an attempt to fight overconsumption. Money shortage drove people to the idea that things could be owned collectively, allowing lenders to gain and borrowers to save more money. This also revived the once forgotten feeling of a big family, reuniting consumers on a personal basis and letting them feel like a member of a huge, national or even international community. We had all that many centuries ago when were living in villages and shared essentials. The history makes a spin—now driving sharing on a whole new level, enhanced with technology and a much wider selection of goods to offer.

Since the major pillar of the sharing economy is consumer-to-consumer trust, the movement needed a source that would provide free information about every potential member in this peer-to-peer sharing community. Social media has taken up this challenge. They allow users to discover more about each other (like seeing if they have common friends and common interests, professional background, etc.) to build more confidence in potential partners, which lets the online connections emerge faster and go firmer in the real-world.

“We couldn’t have existed ten years ago, before Facebook, because people weren’t really into sharing,” commented Nate Blecharczyk, Airbnb’s co-founder, as quoted by The Economist. Basically, peer-to-peer platforms have evolved into social media sites themselves, building a transparent network of connections between real people.

Why is the sharing economy good?

This economical model helps squeeze maximum of a product’s capacity—instead of being used several times by one person, the goods are available for dozens of peers. This allows to save time, money and other resources, generate extra income for the owner and reduce impact on the environment. “Millennials, the ascendant economic force in America, have been culturally programmed to borrow, rent and share. They don’t buy newspapers; they grab and disseminate stories a la carte via Facebook and Twitter. They don’t buy DVD sets; they stream shows. They don’t buy CDs; they subscribe to music on services such as Spotify or Pandora (or just steal it),” Forbes notes.

Now, the philosophy of collectively consumed goods may be found behind a range of peer-to-peer companies that invite to share a plethora of products and services, ranging from a house (Friends of Friends Travel, Airbnb, Easynest, Tint), money (Prosper, Lending Club) and a car (Lyft, RelayRiders, Sidecar) to skills (SkillShare, Livemocha) dinners (Kitchit, Eatwith), WiFi (Fon) to name a few. The reasons why the sharing economy may drive more benefits than traditional industrial economy are as follows:

1. Economical benefits.

The owner makes money on things that would otherwise rest unused, and the renter gets an opportunity to use things for a limited time without purchasing them. The sharing economy can turn owners of any products into micro-entrepreneurs, so tapping into this movement might be a first step to entrepreneurship. Skills can be shared just like physical goods. This fact has fueled a number of platforms (such as TaskRabbit, Exec and more) that connect people offering and taking paid errands and doing office chores. These efforts translate into huge revenues. In early 2013, Forbes predicted that the revenue flowing through the share economy right into people’s pockets will exceed $3.5 billion this year, and the growth will be more than 25%.

2. Reducing environmental impact.

Multi-use of tools or goods may shorten the life of the asset (but not necessarily), but helps get the most of it instead of letting it rest idle for months and get finally discarded, being replaced by fresher versions or getting expired.

Sometimes you also have to buy the whole thing to use just some part of it—for instance, you have to heat the whole house, pay for sewage utilities and maintenance, etc., while you may not live there 24/7/365. Fast Company claims that “when measuring carbon emissions, home sharing is 66% more effective than hotels where as car sharing participants reduce their individual emissions by 40%.” Peers, a recently-launched community, states that up to 72% of U.S. CO2 emissions can potentially be reduced by sharing cars. Sharing meals with others also helps generate less waste by saving on water, gas, electricity and food products. You may not eat a whole home-cooked pizza or a pack of ice-cream alone and have to send the remaining part to garbage, while sharing the meal would solve the problem.

3. Building stronger communities.

Saving/earning some money and reducing waste are not the only benefits of the sharing economy. Moving from the old models of consumption and ownership, we are pushing the boundaries of the lives and letting more people into their circle. We start interacting with people we would never meet under other circumstances. This model turns consumers into active members of societies, who not only lend or borrow goods but also write reviews and recommendations on their peers within the sharing economy communities, building a more trustful environment and helping the movement flourish.

Watch an awesome presentation at TNW by Loic le Meur, a French entrepreneur and blogger, who highlights the benefits of the sharing economy and reviews start-ups that have already reacted to the trend.

Why may the sharing economy seem unsafe for the traditional market and consumers?

In its recent “Shared Economy” report, Altimeter Group, a consultancy providing research and advisory for companies challenged by business disruptions, states that “An entire economy is emerging around the exchange of goods and services between individuals instead of from business to consumer. This is redefining market relationships between traditional sellers and buyers, expanding models of transaction and consumption, and impacting business models and ecosystems.”

Each new model in economical realities destroys the previous one—this is quite natural. Following this rule, the collaborative consumption disrupts the deep-rooted model of industrial economy based on the “you bought-you use” model. Now, it’s moving towards more the “I/you bought—we use” scheme. Collaborative consumption reduces the amount of purchased goods, too. The sharing economy implies that people exchange more and buy less. This tendency has already impacted the automotive industry. The share of new vehicles purchased by Americans aged 18-34 decreased from 16% in 2007 to 12% in 2012, noted Lacey Plache, chief economist of Edmunds.com. Among others, the commitment to rather borrow than buy has influenced these rates.

It may seem that the sharing economy doesn’t do any good to the modern economy, but in fact it does. For instance, services that allow to rent in and out unused dwellings occasionally increase the city’s income. According to June’s report by Airbnb, the renting-in activity stimulates tourism, supports hosts financially—the micro revenues allow them to cover basic expenses (36% of hosts) and start their own businesses (30%). Shortly before the report was released, Amsterdam’s City Board noted that companies like Airbnb help “make better use of the housing stock, can be a touristic economic stimulus, and apparently fill a need of today’s tourists.”

The report states that the average Airbnb guest spends €179 at local businesses in the Amsterdam neighborhood where they stay. The company has also found that their guests stay in the city 3.9 nights on average and spend €792 during their trip—hotel guests stay 1.9 nights on average and spend €521. Offering affordable accommodation, Airbnb inspires people to visit the city—35% of guests confessed they would not have come to Amsterdam or stayed there for as long without the apartment-sharing service.

Additionally, local authorities claim that people who rent up apartments, cars and tools and perform simple tasks, don’t pay taxes as they would if they were entrepreneurs—so steal a piece of pie from legal businesses and violate the law. In May 2013, an Airbnb host in NYC was found to violate the city’s hotel law—since 2010, apartments and houses in New York can be rent up for a period longer than 29 days. This law regulated an old problem and comes to be quite unjust when it comes to rentals made through Airbnb, the service is actually out of the law’s focus. The same happened to ride-sharing services. Lyft, SideCar and Uber have been fined by the California Public Utilities for “operating as passenger carriers without evidence of public liability and property damage insurance coverage” and “engaging employee-drivers without evidence of workers’ compensation insurance.”

So, in general some of the companies based on the collaborative consumption may not run in line with the law, but it’s just because the law should be revised to fit the new era. Until it’s done, they may remain in “a legal grey area” without doing anything illegitimate.

The other issue is safety. Here, a lot depends on peers themselves as people can regulate the transparency by sharing feedbacks on how neat, skillful, honest, etc., hosts, lenders and performers are. Of course, something may go wrong—a guest may rob a house, a driver might be less experienced than stated, a tool might be broken—but these people are instantly entered into a blacklist and won’t be able to use any of the sharing economy services anymore. Reputation goes above money.

How old brands can adapt to the sharing economy?

Modern brands, traditional businesses and manufacturers will have to be receptive in the realities of the collaborative consumption. As now customers start to borrow (buy) from each other, companies have to find a new way to tap into the movement, letting the sharing cult become part of their selling strategy.

The classification offered by Altmeter Group demonstrates that while recently (in the brand experience era—web) brands used the “one-to-many” model to communicate with customers, now (in the brand experience era—social media) the power is shared between customers and companies with a shift towards the collaborative economy era (Social, Mobile, Payment Systems) when power goes to the consumer.

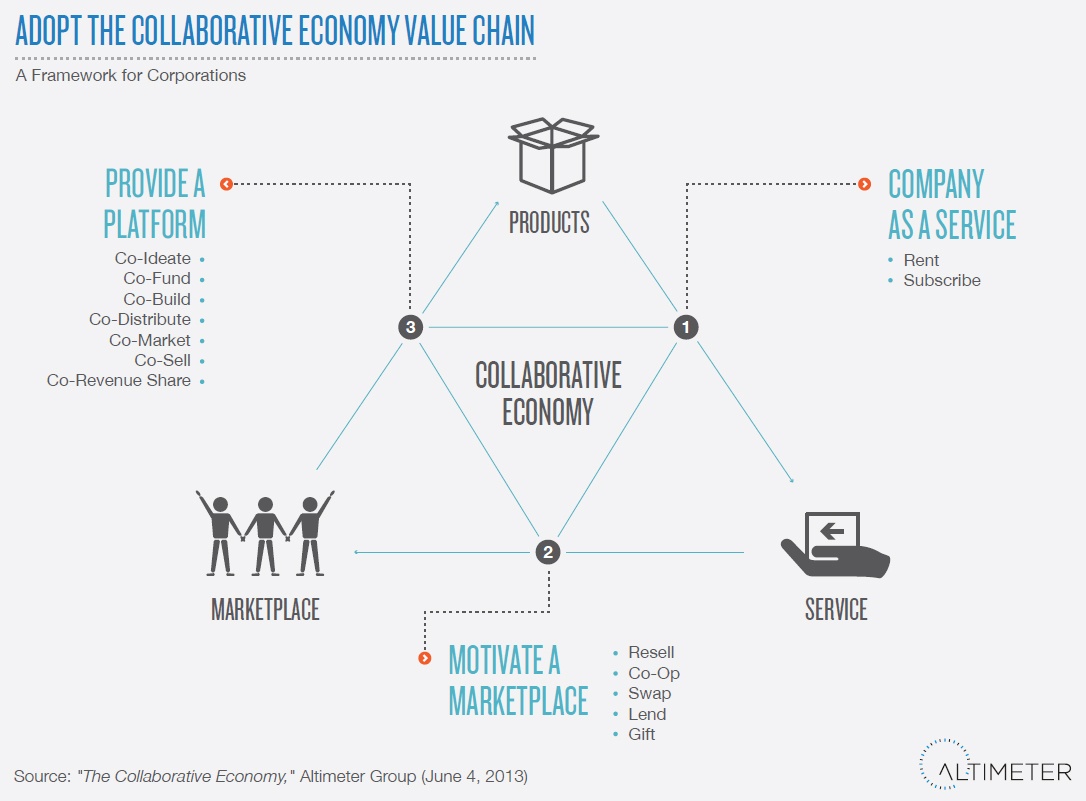

To survive in the new conditions, businesses can adapt three models that correlate with the sharing economy: Company-as-a-Service, Motivating a Marketplace, or Providing a Platform. Some big companies are already doing this.

Company-as-a-Service. This model focuses on developing long-term and repeat relationship with consumers, letting them familiarize with or experience the company’s products.

In 2009, Mercedes-owner Daimler launched the car2go service that allowed to rent Smart Fortwo cars for 38 cents per minute including fuel, insurance and parking. Home Depot, an American retailer of home improvement and construction products and services, also allows consumers of about half of its 2,000 stores to rent tools and trucks, with fees starting at $19. Citibank supports the Citibike NYC-based bike-sharing program.

Motivating a Marketplace. This is about adding a new value to transactions between customers, urging sustainable behaviors through encouraging people to share what they own.

In late 2011, Patagonia encouraged its consumers to resell the apparel they didn’t want to wear anymore on eBay. The initiative was launched under the “buy used and sell what you don’t need” banner. In 2010, IKEA started to sell its second-hand furniture in Sweden to help extend the life of the affordable interior pieces and make them yet cheaper. H&M moved from selling to giving: in early 2013, the retailer encouraged consumers to donate their clothing from any brand as part of the “Long life fashion!”initiative. The items were to be recycled or re-worn, depending on their condition. Contributors received a £5 voucher to redeem as a reward.

Providing a Platform. This requires sourcing the power of the crowd to improve the business functions and products by allowing them to create their own product and establish connections. Companies should act as the ground for new ideas, inspire a new spin of conversation between consumers with no brand specifically involved into it.

MyStarbucksIdea invites the coffee brand fans to share ideas and make their consumer experience even better. eBay, Etsy, and Kickstarter connect users, letting them easily sell, buy and invest. The peer-to-peer activity is not always centered around money—the recently launched platform Yerdle, founded by Walmart, Saatchi&Saatchi and Zipcar veterans, allows to give away and lend stuff for free.

What do we need to help the sharing economy thrive?

The collaborative consumption as the ruling power of the society might seem quite utopian and communistic, nevertheless, it is growing in developed countries now and will probably come forward in emerging markets soon. It doesn’t seem to dominate the world in the coming decade—millions of people might not want to let a stranger touch and use things they’ve worked hard for. But it’s obviously the model which should be adopting, at least to oppose consumerism that erodes cultures and personalities. A viable sharing economy is impossible without three major components:

1. Enhanced technology. Since trust is the driving force of the sharing economy, technology must let people get the transparent and up-to-date information about a lender and a borrower. Without it, the system collapses.

2. High quality of products. Manufacturers should produce less stuff that would be more durable and attractive. A shared product must be created with “multi-ownership” in mind so that many people could use it exhaustively. That would raise the cost of production and prices, too.

3. High moral values. To let strangers into your apartment and lend them a car, give away (not just sell) the stuff you don’t need, share skills for no money, etc., people have to overcome their greedy mindset. They are to embrace non-consumerism philosophy and be more open to new opportunities, which won’t add to their income, but broaden their intellectual horizons.

About the Author

Anna Rudenko is News Editor and Features Writer at Popsop, where she covers philanthropy, future technology and the environmental pulse of the globe. She is an art films aficionado, crafter, avid vegetarian, and sustainability enthusiast who does her best to bring positive change into the world around.